Data Analysis

Pre-Test

Q1. I enjoy playing games (analogue or digital)

Since the mean (4.64), median (5), and mode (5) are all relatively high, you can infer that most respondents strongly agree or agree that they enjoy playing games. The fact that the mode and median are both 5 suggests that the majority of responses are clustered at the highest end of the scale, indicating a strong preference for gaming among participants.

- The mean being slightly lower than the median and mode suggests a slight left skew (some responses lower than 5 are pulling the average down).

- Most participants enjoy games: The high central tendency values suggest that gaming is a common and well-liked activity.

- Minimal disagreement: There are likely very few low ratings (1s or 2s), reinforcing that negative or neutral attitudes toward gaming are uncommon in the sample.

- Relevance for the study: If the study involves game-based learning or gamification, this is a positive indicator that students are receptive to games as an educational tool.

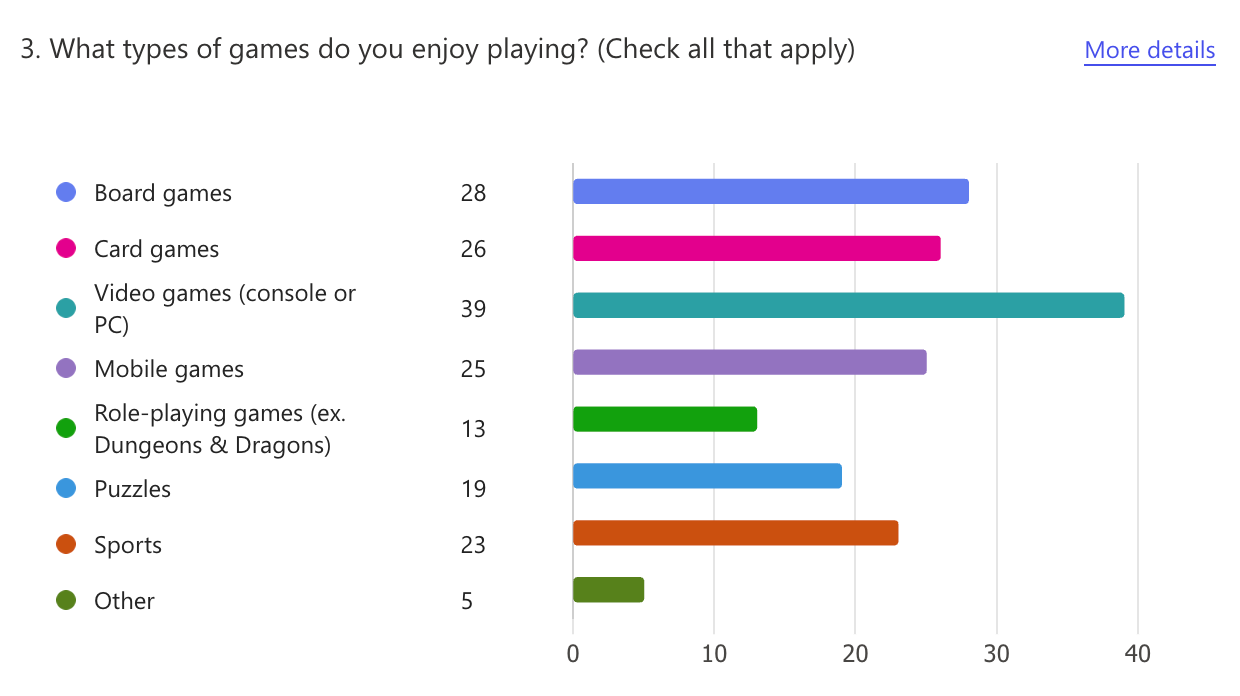

Q2. What types of games do you enjoy playing?

| Game Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Total | 42 |

| Video games (console or PC) | 39 |

| Board games | 28 |

| Card games | 26 |

| Mobile games | 25 |

| Sports | 23 |

| Puzzles | 19 |

| Role-playing games (ex. Dungeons & Dragons) | 13 |

| Mind/strategy games | 1 |

| VR | 1 |

| Strategy | 1 |

| drinking games! | 1 |

| Boulder problems (rock climbing) | 1 |

Given that the research focuses on peer code review, self-determination theory, and game-based learning in computer science education, here’s how the game preference data connects to the research:

-

High Engagement with Games (Strong Suitability for Game-Based Learning)

- 39 out of 42 respondents enjoy video games (console or PC), and many also enjoy board games (28) and card games (26).

- This suggests that the student population is highly receptive to games, making game-based learning (GBL) an appropriate and engaging instructional strategy.

- The prevalence of board and card games could also support the design of a peer feedback card game, reinforcing the idea that the approach aligns with student interests.

-

Potential for Motivation via Game Mechanics (Self-Determination Theory)

- Self-determination theory (SDT) emphasizes autonomy, competence, and relatedness as key factors for intrinsic motivation.

- Since many students already enjoy gaming, the game-based peer review system may leverage intrinsic motivation rather than relying solely on external incentives.

- The fact that both digital and analogue games are well-represented suggests you could incorporate mechanics from both (e.g., digital badges for competence, cooperative/competitive elements for relatedness, and choices for autonomy).

-

Reinforcing Peer Feedback Through Familiar Mechanics

- Since many students enjoy strategy-based games like board/card games, they may already have experience with structured rules, decision-making, and turn-based interactions—elements you can integrate into the peer feedback game.

- If students already enjoy structured gameplay, it suggests they might engage well with a game-like system that provides clear feedback loops and progression mechanics.

-

Designing the Peer Feedback Game: Digital vs. Analogue

- Since video games are the most popular but many students also play board and card games, the game can incorporate both digital and physical mechanics:

- A digital leaderboard or point system to track feedback quality.

- A physical or digital card game format where students exchange feedback through structured prompts.

Conclusion: Strong Justification for a Game-Based Feedback System

- The overwhelming preference for games in general reinforces the pedagogical viability of game-based learning in the course.

- The diversity in game preferences suggests flexibility: Some students may engage more with digital elements, while others might appreciate structured, turn-based analogue mechanics.

- This data supports the feasibility of integrating game mechanics into peer code review, aligning with SDT principles to enhance motivation and engagement.

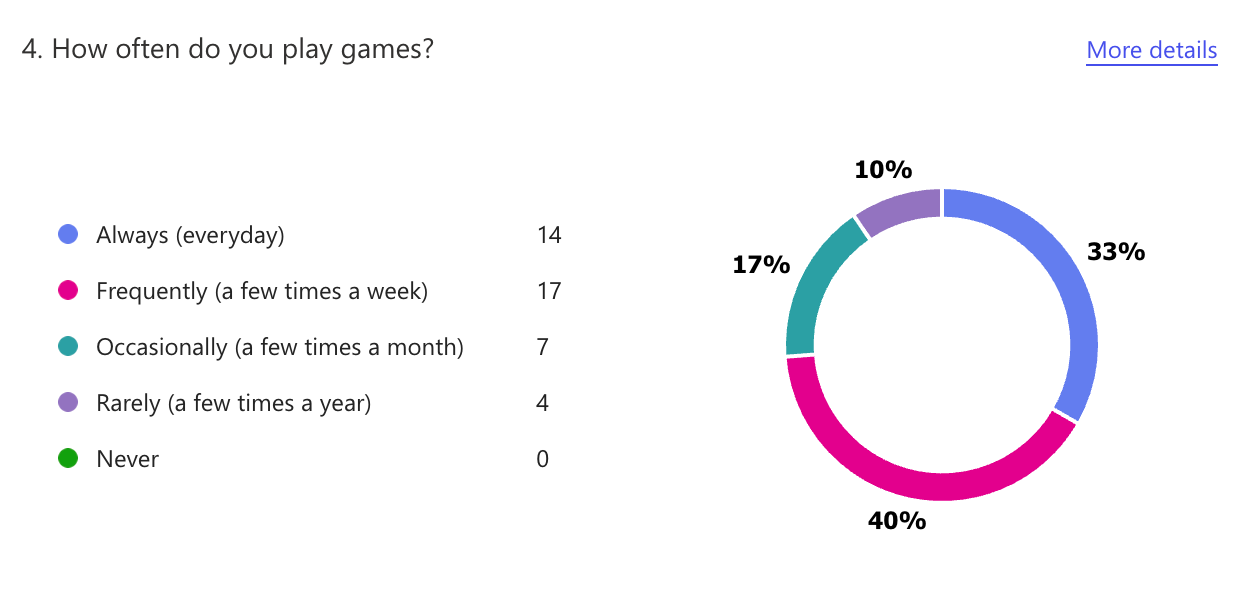

Q3. How often do you play games?

| Frequency | Count |

|---|---|

| Frequently (a few times a week) | 17 |

| Always (everyday) | 14 |

| Occasionally (a few times a month) | 7 |

| Rarely (a few times a year) | 4 |

- Frequent Gaming Habits Support Game-Based Learning (GBL)

- Most students play games frequently (17 play weekly, 14 play daily), indicating they are comfortable engaging with game mechanics.

- This strengthens the justification for using game mechanics in peer code review, as students are likely familiar with progression systems, competition, and strategic decision-making.

- Intrinsic Motivation via Familiar Structures (Self-Determination Theory)

- Since gaming is already a regular part of their lives, integrating peer feedback as a game aligns with an activity they enjoy.

- This could increase intrinsic motivation by making feedback feel like a game challenge rather than a chore.

- Balancing Design for Less Frequent Players

- A minority (7 play monthly, 4 rarely play) may not engage with overly complex game mechanics.

- My design should ensure onboarding is smooth and feedback tasks are intuitive, even for those who don’t game often.

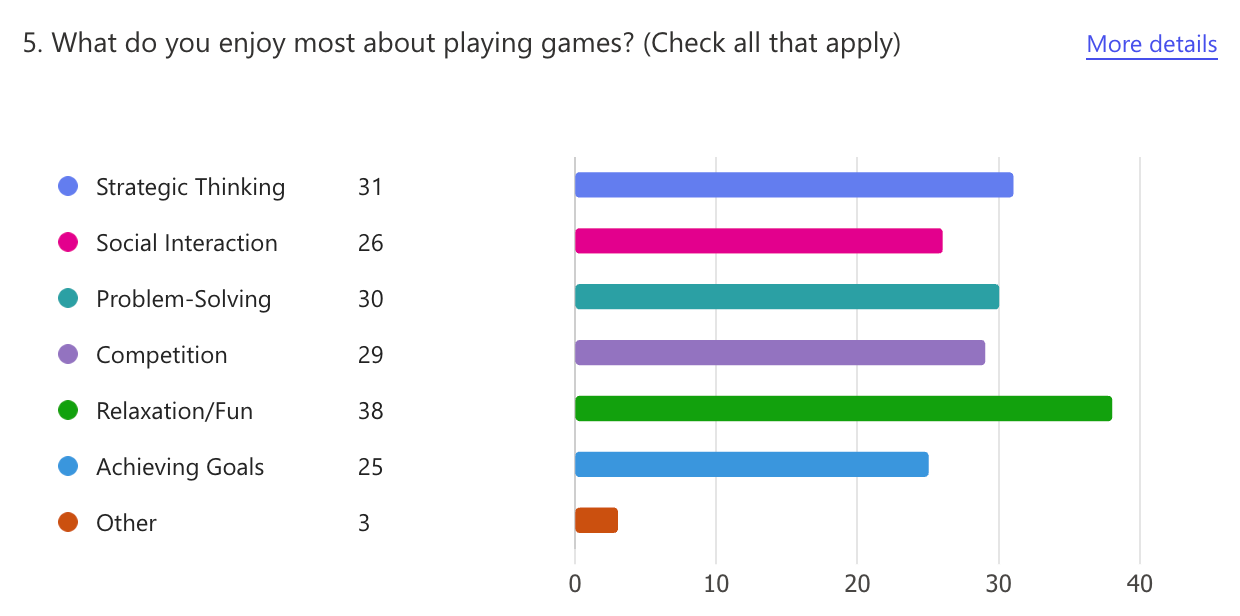

Q4. What do you enjoy most about playing games?

| Enjoyment Factor | Count |

|---|---|

| Total | 42 |

| Relaxation/Fun | 38 |

| Strategic Thinking | 31 |

| Problem-Solving | 30 |

| Competition | 29 |

| Social Interaction | 26 |

| Achieving Goals | 25 |

| immersion | 1 |

| Creativity | 1 |

| Story (video games) | 1 |

- High Engagement with Problem-Solving & Strategy → Supports Peer Code Review

- Strategic Thinking (31) and Problem-Solving (30) are major reasons why students enjoy gaming.

- This aligns well with peer code review, which requires critical thinking, evaluation, and decision-making—skills they already value in games.

- Relaxation & Fun as Key Motivators → Enhancing Feedback Through Gamification

- Relaxation/Fun (38) is the most cited reason for playing games.

- If peer feedback feels engaging rather than stressful, students may participate more actively and provide better-quality reviews.

- Incorporating Competition for Motivation (Self-Determination Theory)

- Competition (29) is a strong motivator, suggesting that leaderboards, ranking systems, or progress tracking could enhance participation.

- This ties into SDT’s competence and relatedness, as students may feel more motivated to improve their feedback to "win" in some way.

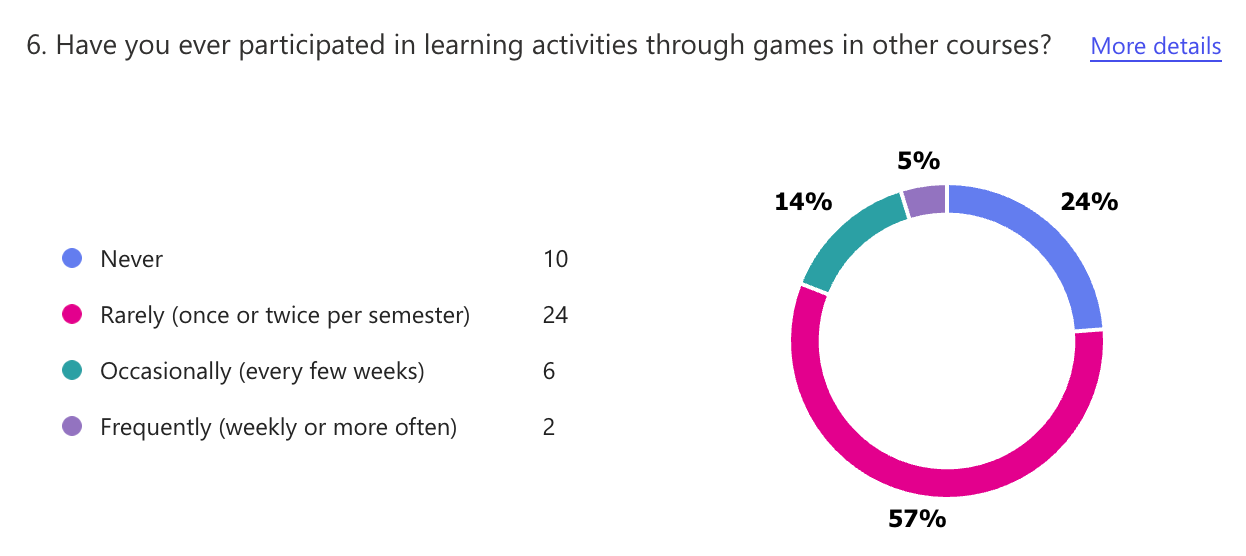

Q5. Have you ever participated in learning activities through games in other courses?

| Previous Experience | Count |

|---|---|

| Rarely (once or twice per semester) | 24 |

| Never | 10 |

| Occasionally (every few weeks) | 6 |

| Frequently (weekly or more often) | 2 |

- Limited Prior Exposure to Game-Based Learning (GBL)

- Most students have rarely (24) or never (10) participated in game-based learning.

- This suggests that the peer feedback game might be a novel experience, requiring clear onboarding to ensure students understand how it works.

- Potential for Increased Engagement

- Since many students enjoy games but haven’t experienced GBL much, this presents an opportunity to introduce an engaging and effective new learning strategy.

- Their lack of prior exposure may lead to curiosity or skepticism, so explaining why and how the game improves feedback will be key.

- Designing for Scalability & Accessibility

- With only 2 students reporting frequent GBL experience, most learners will need gradual scaffolding.

- This aligns with Self-Determination Theory’s autonomy support—giving students freedom to explore the mechanics without overwhelming them.

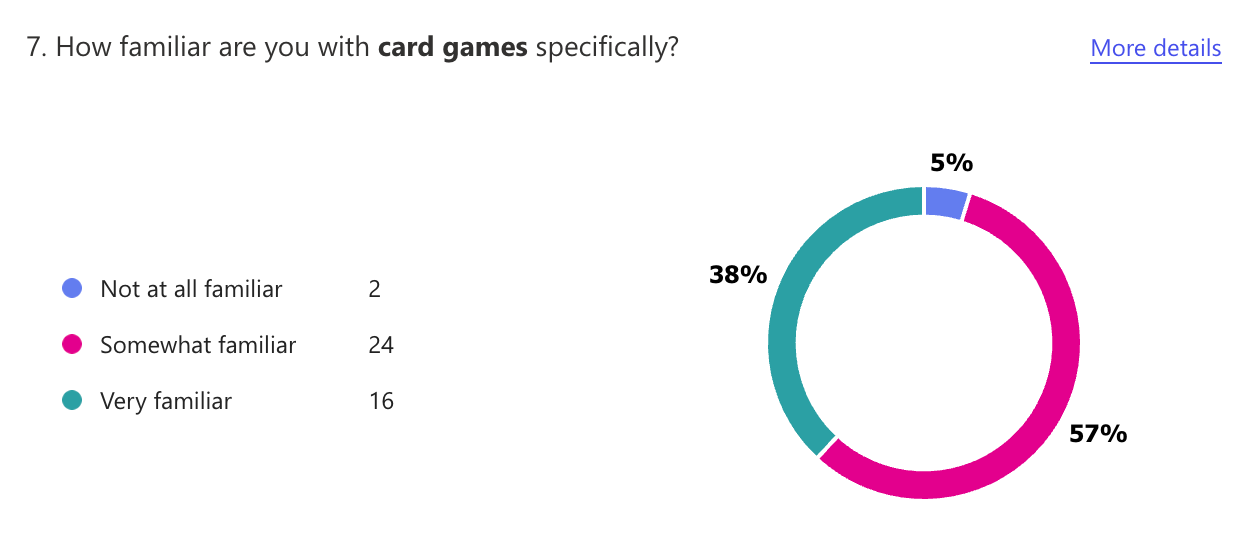

Q6. How familiar are you with card games specifically?

| Familiarity Level | Count |

|---|---|

| Somewhat familiar | 24 |

| Very familiar | 16 |

| Not at all familiar | 2 |

- Most Students Are Familiar with Card Games → Lower Learning Curve

- 24 students are somewhat familiar, and 16 are very familiar with card games.

- This suggests that a peer feedback card game will not require extensive explanations of basic mechanics.

- Supports Game-Based Learning (GBL) with Minimal Friction

- Since most students already understand how card games work, you can focus on designing engaging mechanics rather than teaching fundamental rules.

- This aligns with Self-Determination Theory’s autonomy principle, allowing students to focus on strategy rather than rule comprehension.

- Considerations for the 2 Students Who Are Unfamiliar

- A small subset (2 students) are not familiar at all.

- Including a quick tutorial or visual guide will ensure inclusivity without slowing down the experience for those who are already comfortable.

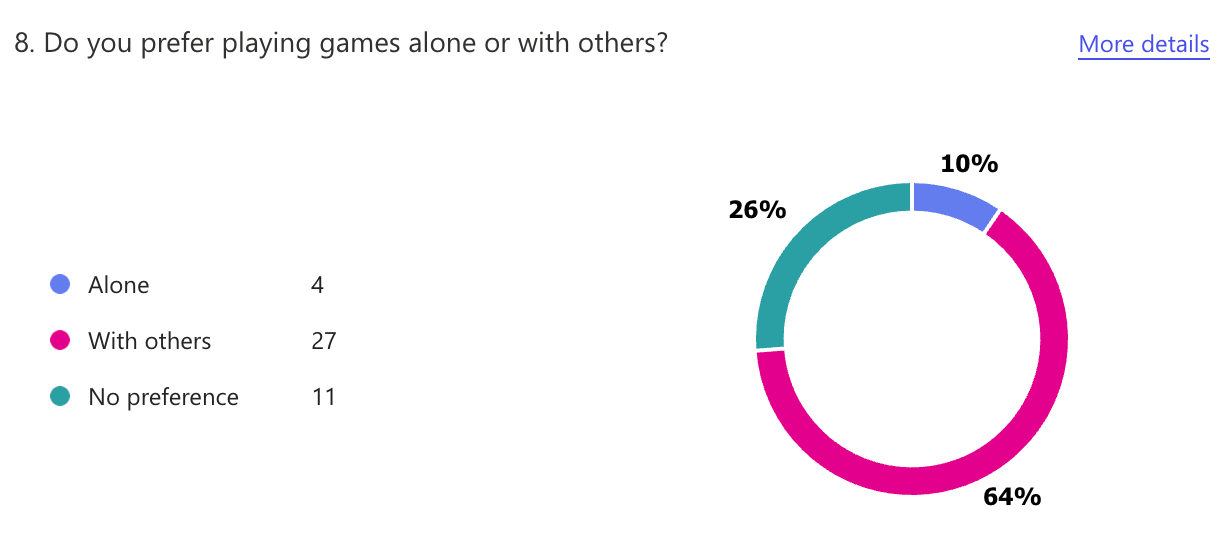

Q7. Do you prefer playing games alone or with others?

| Preference | Count |

|---|---|

| With others | 27 |

| No preference | 11 |

| Alone | 4 |

- Strong Preference for Social Play → Supports Peer Feedback Integration

- 27 students prefer playing with others, suggesting they may be more comfortable with collaborative and interactive feedback activities.

- This aligns well with peer code review as a social learning activity, reinforcing the value of engaging with peers.

- Balancing for Different Preferences

- 11 students have no preference, meaning they could adapt to either solo or group interactions.

- 4 students prefer playing alone, so the game design should ensure that students can engage meaningfully without excessive social pressure (e.g., structured, anonymous feedback options).

- Enhancing Relatedness (Self-Determination Theory)

- Since most students enjoy social gaming, peer feedback mechanisms could leverage cooperative or competitive elements to enhance engagement.

- Features like team-based challenges, leaderboards, or peer voting could reinforce a sense of community.

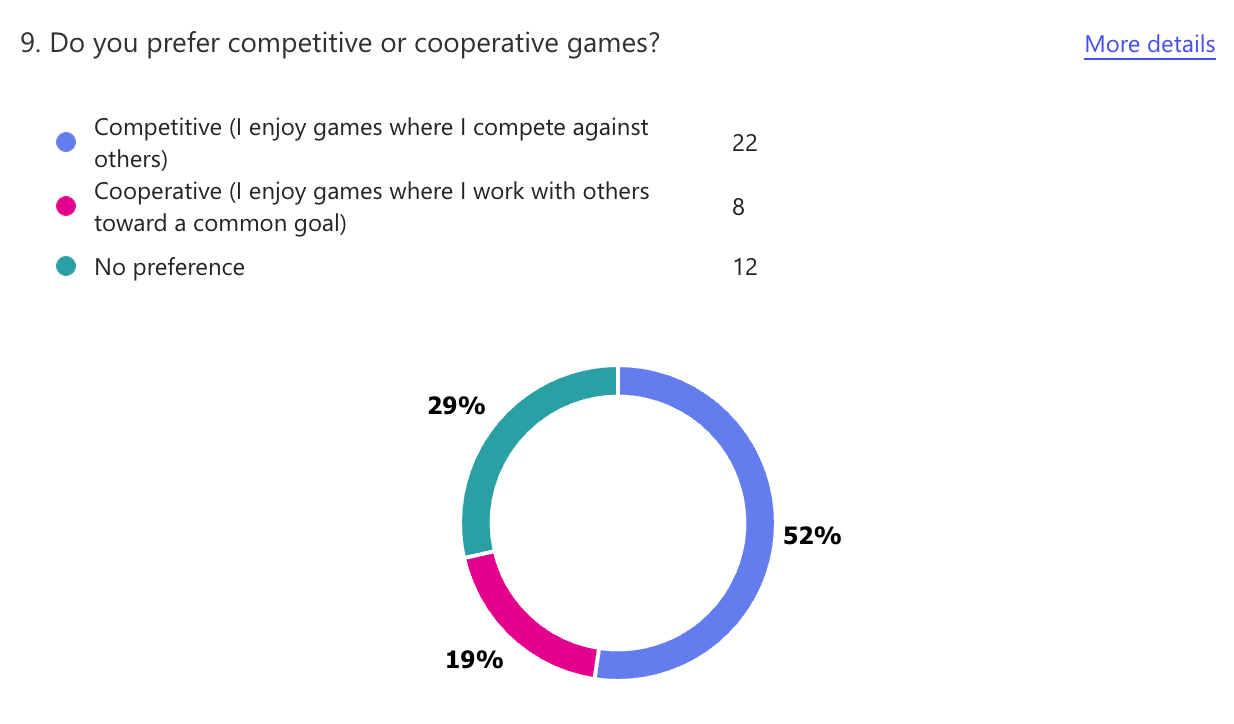

Q8. Do you prefer competitive or cooperative games?

| Game Preference | Count |

|---|---|

| Competitive (I enjoy games where I compete against others) | 22 |

| No preference | 12 |

| Cooperative (I enjoy games where I work with others toward a common goal) | 8 |

- Competitive Elements May Increase Engagement in Peer Review

- 22 students prefer competitive games, suggesting that leaderboards, point-based rankings, or challenge-based peer feedback could enhance motivation.

- This aligns with Self-Determination Theory’s competence principle, where students may strive to improve feedback quality to "win" or outperform others.

- Balancing for Cooperative Players & Neutral Preferences

- 8 students prefer cooperative games, meaning some students may engage better with collaborative peer feedback mechanisms (e.g., team-based peer review or shared goal challenges).

- 12 students have no preference, giving flexibility in incorporating both competitive and cooperative mechanics.

- Designing the Peer Feedback Game

- A hybrid model could appeal to both groups, such as:

- Competitive scoring for quality feedback (e.g., students earn points for well-rated feedback).

- Cooperative team-based reviews, where students collectively analyze and refine code.

- Ensuring students can opt into different styles of engagement may enhance inclusivity.

Post-Test

Q1. I enjoyed playing the card game

The mean (4.79), median (5), and mode (5) for the question "I enjoyed playing the card game." suggest that the vast majority of students had a very positive experience with the game.

-

Strong Validation for Game-Based Learning in Peer Code Review

- A high median and mode of 5 indicates that the game was well-received, reinforcing the effectiveness of game-based learning (GBL) in this context.

- The overwhelmingly positive response suggests that introducing structured game mechanics into peer review enhances engagement and enjoyment.

-

Motivation and Engagement (Self-Determination Theory)

- Autonomy: The game likely allowed students to feel more in control of their feedback process, which is key for fostering intrinsic motivation.

- Competence: If students enjoyed playing, they may have been more willing to refine and improve their feedback skills as part of the game.

- Relatedness: If students had fun, it likely made the peer feedback process feel more social and connected, which may encourage more meaningful interactions.

-

Higher Engagement May Lead to Higher-Quality Feedback

- If students enjoyed the game, they were likely more invested in the peer feedback process.

- Enjoyment can reduce perceived cognitive load, making students more receptive to giving and receiving feedback.

- A fun, game-like approach may have helped reduce anxiety around peer review.

-

Implications for Scaling the Approach

- Since the game was widely enjoyed, this suggests it could be expanded or iterated upon to further enhance learning outcomes.

- If students already enjoyed this implementation, refining mechanics, stakes, or rewards could deepen engagement.

- It may also indicate that game-based peer review could be useful in other courses beyond the own.

Q2. Do you have any feedback about the mechanics or design of the card game?

From the extracted comments, the responses indicate the following key takeaways:

- Overall Positive Reception

- Multiple students described the game as "fun," indicating that they enjoyed the gameplay and found it engaging.

- Some explicitly stated "I love this game" and even suggested publishing it, which reinforces the success of integrating game mechanics into peer feedback.

- Desire for More Depth & Features

- Some students suggested adding "more power-ups" or additional mechanics to enhance gameplay variety.

- This indicates that while the core mechanics were enjoyable, there is room to introduce more complexity or strategic elements.

- Appreciation for Competitive Elements

- A few students mentioned enjoying the competitive aspects of the game, suggesting that scoring, ranking, or challenge-based elements were motivating factors.

- This aligns with the pre-test findings that many students prefer competitive games, reinforcing the idea that leaderboards, point tracking, or win conditions might increase engagement.

After reviewing the responses, the feedback can be grouped into three main thematic categories:

-

Engagement & Fun (Positive)

- Example Responses:

- "It is really fun."

- "I love this game, it’s very fun to play."

- "It is pretty fun. Publish the game:)"

- Implications:

- The game successfully made peer feedback engaging, validating the game-based approach.

- High enjoyment suggests that students may be more motivated to engage in the feedback process.

-

Suggestions for Improvement (Expansion)

- Example Responses:

- "I feel like there should be more power-ups in the game."

- Implications:

- Students may appreciate added mechanics or depth to keep the experience fresh.

- I could explore adding different power-ups, new challenges, or more player agency in future iterations.

-

Competitive & Strategic Elements (Motivation)

- Example Responses:

- "I like the competitiveness of the game."

- Implications:

- Some students were particularly motivated by competition, which aligns with their preference for competitive games.

- Consider enhancing scoring mechanisms, challenges, or ranking systems to deepen engagement.

Next Steps & Recommendations

- Maintain the fun and engaging aspects that students enjoyed.

- Consider adding mechanics (e.g., power-ups, new rules, or additional strategy layers) to increase replayability and depth.

- Explore competitive elements carefully, ensuring that students who prefer collaboration are still engaged.

Q3. Did participating in the card game influence the approach to giving or receiving peer feedback?

Positively Motivated by the Game (21 responses)

These students explicitly stated that the game increased their motivation, engagement, or effort in peer feedback.

Example Responses:

- "It gave me an incentive to put more effort and details into my peer feedback than before."

- "100%, before I only put ‘good job’ or ‘error in x.js’ but now I went in-depth knowing it would give me an edge while playing the game."

- "Yes, I spent more time correcting other people’s assignments."

- "Of course, by nature, I am quite competitive, so my goal was to get the most amount of cards available. Previously, I would peer grade as quickly as I could, whereas now I did it properly, reading through code to make sure things worked as intended and as efficiently as they could."

Relevance to Research:

- This supports the idea that game-based learning can enhance engagement in peer review.

- The findings align with Self-Determination Theory (SDT), particularly in competence (students improving their feedback skills to gain rewards) and autonomy (taking more initiative in their reviews).

- Some students were strategically adapting their feedback behavior to gain better in-game advantages, reinforcing the motivational pull of the game.

Neutral or Minimal Impact (8 responses)

These students acknowledged the game but did not feel it significantly changed their peer feedback approach.

Example Responses:

- "Not really, but I did find the concept fun."

- "It didn’t pose too much of an impact on my assessment of peers’ work."

- "Knowing that the cards I would get for the card game was impacted by my peer review assessment, it didn’t really impact the way I graded people or in the game."

- "Not necessarily. My approach for giving peer feedback is being as fair as possible, and I don’t let the thought of it affecting the card game sway my decisions."

Relevance to Research:

- Some students were already intrinsically motivated to provide thoughtful peer feedback, suggesting that game-based incentives are not universally necessary.

- Others indicated that they weren’t thinking about the game while reviewing, but still enjoyed the reward.

- This suggests that peer review improvement may not be fully dependent on game mechanics, but a subset of students still found the added layer engaging.

Increased Awareness But Not Strongly Motivating (6 responses)

These students noted a change in their thought process or effort level, but not necessarily in a way that strongly altered their feedback approach.

Example Responses:

- "The game made me a bit competitive, which affected the way I gave feedback to have a better chance of winning the card game."

- "Yes, the card game influenced me to give more feedback but up to a certain degree. I wouldn’t go too out of my way, but if it was an easy bug fix that I could provide, I would give them the feedback on it."

- "Knowing that you get more yellow action cards definitely prompted me to give more in-depth peer feedback."

Relevance to Research:

- The game subtly reinforced engagement but did not entirely dictate how students gave feedback.

- This group suggests that peer review incentives should be balanced—they can encourage participation, but over-reliance on extrinsic motivation may not be necessary.

- Some students may benefit from additional scaffolding on how feedback quality affects both learning and game outcomes.

Negative or Unclear Impact (4 responses)

These students either felt pressured, confused, or did not have a positive experience with the game in relation to peer feedback.

Example Responses:

- "I forgot to do peer feedback due to having a lot of things going on during the week, but I think in a setting with less stress, I’d be a lot more motivated to give good feedback."

- "Today was the first day that I played the card game, and honestly, I had no idea how it worked, so I never thought of the card game when I was grading before."

- "After the card game, I felt that the bar for effort in grading was set from our previous results. It put pressure to either match how we graded previously or improve, while discouraging doing any less than that. So it was more motivating in my opinion."

Relevance to Research:

- Game-based incentives should not create undue stress—some students mentioned feeling pressure to maintain past grading efforts, which could be counterproductive.

- New players may need a clearer introduction to ensure they understand how the game influences peer review.

- While peer review should challenge students to improve, balancing competition with constructive, low-pressure engagement is key.

| Category | Number of Responses |

|---|---|

| Positively Motivated by the Game | 21 |

| Neutral or Minimal Impact | 8 |

| Increased Awareness But Not Strongly Motivating | 6 |

| Negative or Unclear Impact | 4 |

- Game-based peer review can significantly increase motivation for a majority of students (21 out of 39).

- Many students put more effort into feedback, reviewed code more deeply, and refined their comments.

- This supports Self-Determination Theory’s motivation principles, showing that competence-driven incentives can enhance peer learning.

- Some students (8) were neutral, meaning motivation strategies should be flexible.

- These students may already have strong intrinsic motivation for feedback.

- This suggests that while game mechanics enhance engagement, they should not replace intrinsic academic motivation.

- A small group (6) noticed the impact but were not deeply influenced.

- They engaged more with awareness-based motivation rather than deep behavioral change.

- The game may have made feedback feel slightly more structured or engaging, but not necessarily transformative.

- A minority (4) felt pressured or confused, suggesting refinements to onboarding and pacing.

- The game should be clearly introduced, and students should feel in control rather than pressured.

- Ensuring low-stakes engagement with high learning value will balance competition and collaboration.

Next Steps & Potential Enhancements

- Refine onboarding for new players to ensure all students understand how the game integrates with feedback.

- Introduce scaffolding for peer feedback improvement so students feel they have a clear path to progress in both feedback quality and game strategy.

- Explore personalization—some students may prefer competitive peer review, while others might benefit more from cooperative structures.

- Maintain a balance between motivation and stress by ensuring that game elements enhance, rather than pressure, participation.

SDT Breakdown

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) posits that motivation is driven by three core psychological needs:

- Autonomy–Feeling in control of one’s actions.

- Competence–Feeling capable and improving skills.

- Relatedness–Feeling socially connected to others.

From the 39 responses, we can categorize their alignment with these SDT components.

- Competence: 24 responses

(Students who increased effort, improved feedback quality, or were motivated by the challenge)

Example Responses:

- "It gave me an incentive to put more effort and details into my peer feedback than before."

- "100%, before I only put ‘good job’ or ‘error in x.js’ but now I went in-depth knowing it would give me an edge while playing the game."

- "I now want to give better feedback to receive better cards and beat the others."

- "Knowing that I wasn’t dealt the best hand of yellow action cards (which means that my feedback was lacking in some way), it made me more implicated in giving feedback. I spent more time thinking about what I could say and added more details."

- "Of course, by nature, I am quite competitive, so my goal was to get the most amount of cards available. Previously, I would peer-grade as quickly as I could, whereas now I did it properly, reading through code to make sure things worked as intended and as efficiently as they could."

SDT Interpretation:

- These students responded positively to competence-based motivation, meaning the game made them feel capable and driven to improve their feedback skills.

- The clear link between feedback quality and game outcomes pushed them to engage more deeply.

- Competence-driven learning is crucial in skill-based domains like programming, reinforcing the effectiveness of game-based feedback mechanisms.

- Autonomy: 7 responses

(Students who acknowledged the game but did not feel it dictated their feedback approach)

Example Responses:

- "Not necessarily. My approach for giving peer feedback is being as fair as possible, and I don’t let the thought of it affecting the card game sway my decisions."

- "Knowing that the cards I would get for the card game was impacted by my peer review assessment, it didn’t really impact the way I graded people or in the game."

- "Not really, I just noted what they lost points for and how they could fix it if it wasn’t too long to fit in the text."

SDT Interpretation:

- These students had high intrinsic motivation, meaning they already felt in control of their learning and didn’t need the game as an external motivator.

- SDT suggests that external motivators should support, not replace, intrinsic motivation—this group highlights that balance.

- While the game may not have changed their process, it still provided autonomy-supportive reinforcement by letting them engage on their own terms.

- Relatedness: 6 responses

(Students who valued the social, interactive, or competitive nature of the game)

Example Responses:

- "The game made me a bit competitive, which affected the way I gave feedback to have a better chance of winning the card game."

- "I think it was just a fun way to try the best at giving peer feedback."

- "Its a very good game for peer feedback; we learn more and how to participate in group activities and get feedback from others to improve in learning a lot."

- "It’s a fun and unique way of motivating people to put effort in. I wasn’t thinking about it while giving feedback, but it did make me happy that I got a fun little reward for putting in the effort."

SDT Interpretation:

- These students enjoyed the peer-to-peer connection that the game fostered, reinforcing the relatedness principle of SDT.

- Competitive elements enhanced engagement by making feedback feel like a shared challenge, rather than an isolated task.

- Relatedness plays a strong role in collaborative learning environments, and these responses suggest that game-based peer feedback increases student interaction in a meaningful way.

- External Regulation & Pressure: 2 responses

(Students who felt pressured or stressed by the game mechanics)

Example Responses:

- "After the card game, I felt that the bar for effort in grading was set from our previous results. It put pressure to either match how we graded previously or improve, while discouraging doing any less than that."

- "I forgot to do peer feedback due to having a lot of things going on during the week, but I think in a setting with less stress, I’d be a lot more motivated to give good feedback."

SDT Interpretation:

- These students may have experienced controlled motivation, where external factors (game mechanics) created pressure instead of autonomy-supportive engagement.

- While competition can be motivating for some, it should not introduce excessive stress that discourages participation.

- To mitigate this, the game design could incorporate more cooperative elements, or provide alternative ways to engage that don’t rely purely on competitive incentives.

Final Categorization Based on SDT

SDT Category Number of Responses Key Insight

Competence 24 The game encouraged skill-building, making students refine their feedback.

Autonomy 7 These students already had strong intrinsic motivation and engaged on their own terms.

Relatedness 6 The game made peer review feel more social and interactive, increasing engagement.

External Pressure 2 A small number of students felt pressured, suggesting room for improvement in game balance.

Key Takeaways for My Research

-

Competence-driven motivation is the most significant factor (24 students)

- The game incentivized students to analyze code deeper, refine their feedback, and engage more critically.

- This reinforces that game mechanics can effectively scaffold deeper learning in peer review.

-

Autonomy remains important—game elements should support, not dictate, motivation (7 students)

- Some students were already intrinsically motivated to give quality feedback.

- The game should complement their learning process rather than impose strict external rewards.

-

Relatedness adds value—game-based peer review can enhance social learning (6 students)

- The competitive and interactive aspects made feedback feel more engaging and communal.

- Peer learning environments should balance competition and collaboration.

-

A small percentage of students felt pressure (2 students)—stress should be minimized

- While competition can enhance motivation, it should not create anxiety or discourage participation.

- Design adjustments could make the system more inclusive for students who feel overwhelmed.

Potential Enhancements Based on SDT

- Increase Competence Support:

- Provide scaffolding and reflection prompts to help students see their feedback improve over time.

- Offer examples of strong peer feedback so students understand how to progress.

- Autonomy-Supportive Game Design:

- Allow students to opt into different play styles (competitive vs. cooperative mechanics).

- Ensure that external rewards never replace intrinsic motivation.

- Enhance Relatedness in the Game:

- Introduce team-based or cooperative peer review challenges alongside competition.

- Encourage students to discuss feedback strategies within peer groups.

- Reduce External Pressure for Certain Students:

- Ensure that performance tracking is transparent but not punitive.

- Offer low-stakes game iterations where students can experiment with feedback styles without fear of judgment.

Final Thoughts: How SDT Aligns with My Research

- My game-based peer review aligns strongly with SDT’s competence and relatedness principles, confirming its pedagogical value.

- Fine-tuning the balance between extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation will make the system more adaptive to different student engagement styles.

- Game-based learning enhances feedback engagement, making peer assessment more interactive, meaningful, and skill-building.

Likert Scale Pre-Post Comparison

- Independent T-tests were conducted to compare the pre-test and post-test scores for three categories: Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness.

- One-tailed p-values were used since we hypothesized that post-test scores would be higher.

| Category | One-Tailed p-value | Significance | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | 0.0079 | Significant (p < 0.05) | 0.55 (moderate effect) | Meaningful improvement in Autonomy after the intervention. |

| Competence | 0.296 | Not significant | 0.12 (small effect) | No meaningful change in Competence. |

| Relatedness | 0.0295 | Significant (p < 0.05) | 0.43 (moderate effect) | Noticeable improvement in Relatedness. |

- Autonomy significantly improved from pre-test to post-test (p = 0.0079), with a moderate effect size (d = 0.55). This suggests that the intervention had a meaningful impact on students’ sense of control over their feedback.

- Relatedness also showed a statistically significant increase (p = 0.0295) with a moderate effect size (d = 0.43). This indicates that students felt more connected to their peers after the intervention.

- Competence did not significantly change (p = 0.296) and had a small effect size (d = 0.12), meaning the intervention did not have a meaningful impact on students’ perceived competence in giving feedback.

!Pre-Test vs. Post-Test Scores by Category.png

A bar chart showed clear increases in Autonomy and Relatedness, while Competence remained nearly the same, reinforcing the statistical findings.

The intervention significantly improved Autonomy and Relatedness, but did not impact Competence. This suggests that while students felt more in control and connected to their peers, their confidence in the quality of their feedback remained unchanged. I may want to investigate whether additional support is needed to improve their sense of competence.

Research Question Alignment

My research question explores whether the game-based learning intervention influenced students’ perceived competence, autonomy, and relatedness, as conceptualized by Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

My results indicate that the intervention had a significant impact on Autonomy and Relatedness but did not significantly affect Competence. Below, I discuss these findings in relation to SDT.

Autonomy – Significant Increase (p = 0.0079, d = 0.55, Moderate Effect)

SDT suggests that Autonomy is enhanced when learners feel they have control over their learning experiences (Deci & Ryan, 2000). In the study, the game-based learning intervention significantly improved Autonomy, suggesting that the game mechanics (e.g., linking feedback quality to game resources) may have reinforced students’ sense of control over their feedback contributions.

This aligns with previous research on game-based learning, which indicates that gamification elements—such as choice, agency, and meaningful consequences—can enhance Autonomy by giving students control over their progress (Deterding, 2015). My findings suggest that integrating game mechanics into peer feedback effectively supports students’ sense of autonomy.

Competence – No Significant Change (p = 0.296, d = 0.12, Small Effect)

A surprising result is that Competence did not significantly increase, despite the intervention. According to SDT, Competence improves when learners experience success, receive constructive feedback, and are given challenges that match their skill level (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

Possible explanations for this result:

- Lack of sufficient scaffolding: If students were unsure how to give effective feedback, they might not have experienced enough mastery experiences to feel more competent.

- Delayed competence gains: It’s possible that competence gains require longer-term practice before students internalize their improvement.

- Game dynamics focused more on motivation than skill-building: While the game influenced engagement, it may not have explicitly improved students’ feedback skills.

These results suggest that while the game encouraged participation, students may still require explicit skill-building activities (e.g., structured training in giving feedback) to develop their perceived competence.

Relatedness – Significant Increase (p = 0.0295, d = 0.43, Moderate Effect)

SDT posits that Relatedness improves when students feel connected to others and perceive their contributions as meaningful (Deci & Ryan, 2000). My intervention led to a significant increase in Relatedness, suggesting that the peer feedback process within the game helped students feel more connected to their peers.

This aligns with research showing that collaborative game-based learning environments can strengthen peer interactions by making social engagement a meaningful component of the experience (Sailer et al., 2017). The game likely helped students see peer feedback as a shared experience rather than an isolated task, which increased their sense of connection with their classmates.

Implications for Game-Based Learning Design

My findings contribute to the understanding of game-based learning interventions in higher education. Based on these results, future iterations of the intervention could be improved by:

- Enhancing Competence Support:

- Providing structured training on effective feedback before integrating it into the game.

- Incorporating real-time feedback or exemplars to help students see what "good feedback" looks like.

- Sustaining Autonomy:

- Allowing students to customize aspects of their feedback process to maintain their sense of agency.

- Offering multiple game paths or strategic choices that further reinforce meaningful control.

- Deepening Relatedness:

- Encouraging more reflective peer discussions on feedback received.

- Creating shared team-based game mechanics where students collaborate on feedback strategies.

My study demonstrates that game-based learning can effectively support Autonomy and Relatedness, reinforcing SDT’s predictions about the importance of agency and social connection in learning environments. However, the lack of significant change in Competence suggests that game mechanics alone may not be enough to build students’ confidence in giving feedback. Future refinements could include explicit skill-building strategies to complement the motivational benefits of gamification.

Code Review Taxonomy Scores

-

Initial Approach: Paired t-Test

- Since each row represents the same student before and after an intervention, a paired t-test was conducted.

- The results showed:

- t-statistic = 3.19

- Two-tailed p-value = 0.0019

- One-tailed p-value = 0.00095

- Conclusion: The one-tailed test indicated statistically significant improvement in feedback quality.

-

Checking Normality of Differences

- The t-test assumes that the differences (Post - Pre) are normally distributed.

- A Shapiro-Wilk normality test on the differences found:

- p-value = 0.0002 (< 0.05), meaning the differences are not normally distributed.

- The histogram and Q-Q plot confirmed this, indicating a deviation from a normal distribution.

-

Non-Parametric Alternative: Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test

- Since normality was violated, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted instead.

- Results:

- Statistic = 641.5

- p-value = 0.0017

- This also indicated statistically significant improvement in feedback quality.

Final Conclusion

- The initial paired t-test was not fully appropriate due to the non-normal distribution of differences.

- However, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test confirmed the same conclusion:

→ Students’ feedback quality significantly improved from Pre to Post.

- This means you can confidently state that the intervention led to higher quality peer feedback, based on statistically significant evidence.

Aligning Peer Feedback Quality Results with Attitudes Toward Feedback & Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

Val Comments

- Mention Q6 in limitations (discussion) section, acknowledge that we don't know if including it would have had an impact on the findings. In future research, they should make sure to measure this. Super quick note, recognize it's there, but no need to go into great detail.

- Discussion starts with a summary of the findings, then the strength of the studies, then limitations

- Based on the pieces I read and put together in the lit review, it allowed me to come up with my hypothesis, in the discussion "based on so and so and so and so, it's consistent with the lit that gaming increases motivation autonomy/competence/relatedness".

- What will be more challenging will be to talk about why students didn't feel more competent

- Tables and figures used in place of sentences that would otherwise be too wordy to understand